by Cory Marsh –

An Exegetical Case Study in John 9 Concerning God’s use of Physical Handicaps

Introduction

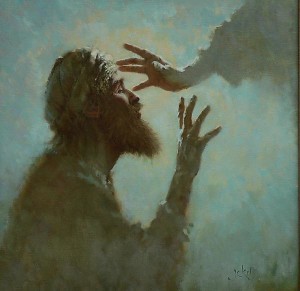

When it comes to theological interrogations, Jesus will not backed in a corner. This is true whether the questioners are antagonists (Matt 22:23-40), or His own disciples as in John 9:2: “And his disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (ESV). Rather than choosing between personal or genetic sin, Jesus presents a third option in v.3 concerning the man τυφλὸν ἐκ γενετῆς (blind from birth, v.1): that God’s power in Christ be shown in him. This miracle was then accomplished when Jesus re-created the man’s eyes (vv.6-7) and thus demonstrated in tangible form that He, in fact is, the very “Light of the world” (8:1;9:5). Yet it is this particular episode that marks what some consider to be an exegetical and theological problem. Specifically, with Jesus’ (via John’s) use of the adversative conjunction, ἀλλ᾽ (but), the traditional punctuation of vv.3–4 are called into question. Basically, the question asked is: when should verse 3 end and verse 4 begin? Or, more technically, should vv. 3-4 be repunctuated as to make v. 3 a single clause, with the remaining clauses continuing in v. 4 after being initiated by the conjunction, ἀλλ᾽? If so, this would convert the familiar adversative or contrasting function of “but” into an introductory conjunction initiating a whole new set of clauses. And if this be the case, then the traditional mainline versification found in most English New Testaments versions of John 9:3-4 are misleading at best, and indeed erroneous at worse. Yet some, in an attempt to escape Jesus’ stated purpose for the blind man’s handicap—as marked by the conjunction ἵνα (so that) in v.3—have in fact chosen this route.

Because of the theological implications of the Greek grammar—that God would actually allow a person to experience a life-long deformity for the sole purpose of His Son one day healing him and thus reveal the glory of God—some scholars have chosen to repunctuate these two verses in an attempt to get God “off the hook.” Yet by doing so, the problem is not solved in any real sense and only leaves more open ended questions.

Because of the theological implications of the Greek grammar—that God would actually allow a person to experience a life-long deformity for the sole purpose of His Son one day healing him and thus reveal the glory of God—some scholars have chosen to repunctuate these two verses in an attempt to get God “off the hook.” Yet by doing so, the problem is not solved in any real sense and only leaves more open ended questions.

It is the contention of this author that vv.3 and 4 of John 9 are in fact punctuated correctly in the majority of English translations, and that the purpose of the blind man’s congenital deformity was indeed ordained by God in order to one day glorify Himself through Christ’s healing of it.

The Problem

What did Jesus intend when He stated the word ἀλλ᾽ (but) in John 9:3? In 644 occurrences throughout the New Testament,[1] the logical function of this word dictates its dominate usage as a contrasting (or adversative) conjunction. As such, it can be translated but, rather, however. Although this conjunction can more broadly be considered a connective conjunctive, as it still connects one thought to another, Wallace states this particular contrasting conjunction “suggests a contrast or opposing thought to the idea to which it is connected.”[2] Contextually, with the use of this contrasting conjunction in v.3[3], Jesus is setting up the purpose (or reason) for the man’s congenital blindness as marked by the immediately following word, the conjunction ἵνα (so that). Yet, as mentioned above, there are some who believe this poses both an exegetical and theological problem. Exegetically, the problem can be stated like this: “Should v. 4 actually begin with ἀλλ᾽ (but)? If so, that would cause this conjunction to serve an introductory use rather than adversative which violates its otherwise dominate usage. Theologically, if this conjunction should be repuncutated to introduce v.4, than the meaning of the text is altered substantially. By placing the conjunction ἀλλ᾽ introductorily in v.4, rather than its traditional placing in v.3, what would then be bypassed is the very reason (or purpose) for the man’s congenital blindness as marked by the subordinate conjunction, ἵνα: “so that the works of God [i.e., eye sight given] be displayed in him.”[4] Or in other words, by placing αλλα as introducing v.4, as in the examples below, God would not have purposed the man to be born blind in order that Jesus would one day heal him and thus glorify God in the miracle. If this view is to be accepted, then Jesus entirely ignored this implication of the “problem” by focusing solely on the works. Thus, the verse would then read as follows:

|

3Neither did this man sin nor his parents.4 But, so that the works of God may be displayed in him, we must work the works of Him who sent Me while it is day. |

Predispositions Guiding Exegesis

There are several Johannine scholars who support the view that ἀλλ᾽ would be better placed as an introductory conjunction initiating v.4. The subordinate conjunction ἵνα (so that, that) would then serve to set up the purpose of Jesus and His disciples working good works to help the man born blind. Kruse states the issue this way:

Verses 3 and 4, punctuated as they are in the NIV (and most other English versions and modern Greek texts), present an unattractive theodicy. They imply that God allowed the man to be blind so that many years later God’s power could be shown in the restoration of his sight. However, it is not necessary to read the text this way.[5]

Kruse is not alone in his sentiments. In the 1940s while giving lectures on John’s Gospel at the Church of the Open Door in Los Angeles, as well as Westminster Chapel in London, noted British Bible scholar, G. Campbell Morgan, expressed his disdain for the traditional placing of ἀλλ᾽ (but) in v.3: “If that punctuation is to be accepted, then Jesus meant that this man was not blind because of his own sin or his parents’, but in order to give God an opportunity to show what He could do with a blind man. I absolutely refuse to accept this interpretation …. I ventured to repunctuate it.”[6] Along with Kruse and Campbell, another noted Johannine commentator, Gary Burge, likewise supports repuncuating vv. 3 and 4: “The ‘purpose clause’ of 3b … can just as well be applied to 9:4, and no doubt it should.”[7]

What should be noted regarding the above contentions is the common theme running through each of these scholars’ reasoning for rejecting the traditional view of vv. 3 & 4. That theme is not based on purely grammatical-historical grounds, however, but rather theological bias. Instead of taking the grammar of the text at face value, each of the above scholars expose in their explanations of moving ἀλλ᾽ (but) to introduce v.4 as having scorn for the theological implications of the traditional placing. For instance:

Kruse: “Verses 3 and 4 punctuate as they are … present an unattractive theodicy.”[8]

Morgan: “If that punctuation is to be accepted [i.e., the traditional placing] … I absolutely refuse to accept that interpretation …. Involved in [the] answer [i.e., the alerted placing], is a revelation that blindness from birth is not the will of God for any man.”[9]

Burge: “While a sound theology cannot doubt God’s sovereignty to do as he pleases, thoughtful Christians may see this as a cruel fate in which God inflicts pain on people simply to glorify himself.”[10]

None of the above men seem to consider God sovereignly determining a man with congenital blindness in order that He may be glorified through it when His Son reveals His power by re-creating the man’s eyes—both physical and spiritual (cf. 9:38). In fact, a similar instance and purpose is found just two chapters later with the death of Lazarus in John 11:4: “When Jesus heard it, He said, ‘This illness is not for death, but [ἀλλ᾽] on behalf of the glory of God, so that [ἵνα] the Son of God may be glorified through it.”[11]

Theological Presuppositions Guiding Exegesis

Besides each men revealing their bias for boldly re-punctuating the Greek text—in order to escape the supposed theological implication—each of them additionally make a fatal flaw in their bias: they equate blindedness with evil. Indeed, this presupposition should itself be analyzed. In question form, it can be asked: Why is it necessary to consider blindness evil or even painful? What explicit Scriptural texts can serve to prove that if one is blind, the person is experiencing some sort of evil and suffering? [12] Granted, the biblical canon does not paint blindness in an overtly positive light, yet it equally does not present it as pure evil or suffering either. It seems to this author each of the above scholars’ attempt to change the traditionally held Greek construction of John 9:3-4 has a purpose which arrived dead on a arrival. Before one can dare change (re-punctuate) the Greek text—especially in order to fit a preferred theological assumption—that assumption better be proved at the outset.

While Burge tips his hat to God’s sovereignty in the last reference above, he immediately cancels it in the second half of his sentence by pitting “thoughtful Christians” against those who would disagree with him. For whatever reason, he seems to have overlooked key texts explicitly declaring God’s sovereignty, even over blindness. He is not alone, as Morgan is probably the most dogmatic when he boldly asserted “blindness from birth is not the will of God for any man.” In stark contrast to this claim, Moses recorded God as saying: “Who has made man’s mouth? Who makes him mute, or deaf, or seeing, or blind? Is it not I, the LORD?” (Ex 4:11 ESV). Where in this explicit reference to God’s sovereignty over bodily handicaps does it even remotely imply that God would “never will a man to be born blind”? The Scripture record in fact testifies to the exact opposite. Additionally, where is it implied that blindness is a form of evil, pain, or suffering? In contrast, the Scripture record shows kindness to the blind as a judicial law that Israel was commanded to reflect: “You shall not curse the deaf or put a stumbling block before the blind, but you shall fear your God: I am the LORD” (Lev 19:14 ESV; cf. Deut 27:18).

The Purpose for the Handicap Revealed

Is God absolutely sovereign over people’s handicaps, even blindness? Yes. Even if that purpose was not for punishment or suffering? Yes. This is not unusual in the Gospels. As mentioned above, a few chapters subsequent to this episode, John gives his readers the explicit purpose for why Jesus’ dear friend Lazarus was ill: “But when Jesus heard [that Lazarus was ill], he said ‘this illness is not for death, but for the glory of God, so that [ἵνα] the Son of God may be glorified through it’” (John 11:4). Therefore, could God have purposed the man in John 9 to be born blind in order to one day reveal Himself to that particular man, and with him, to the world at large (as its recorded in the Bible for all to see)? Yes, and it is for this purpose that the man’s handicap was ordained by God.

Conclusion

Taking in all the above considerations, it seems more appropriate to allow the text to speak for itself, even if it presents an uncomfortable situation. Thus, based on the exegesis above, MacArthur leaves us with the only simple, clear option as to why God had this man be born blind: “God sovereignly chose to use this man’s affliction for His own glory.”[13] The Greek is what it is, and any theological bias or presuppositions we may hold should not hinder its message. God ordains and uses them to serve His greater purposes, as He did with this man τυφλὸν ἐκ γενετῆς (blind from birth)—and is able to do so without a hint of committing evil (Rom 8:28; James 1:13). Therefore, the traditional placing of ἀλλ᾽ in v.3, as reflected in the major English translations is accurate reflecting the subjunctive conjunction ἵνα stating the actual purpose of the man’s blindness: that the works of God, as shown in Jesus’ miracle, would one day be displayed in him.

[1] Out of all the 644 occurrences in the NT, the full form ἀλλά is used 421xs while the apocopated ἀλλ᾽ (as in John 9:3) is used 223xs. There is no difference in meaning between the two.

[2] Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 671.

[3] It should be noted that according to Fredrick W. Danker, ed., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 2001), s.v. “ἀλλά”:

“The use of ἀλλά in the Johannine literature is noteworthy, in that the parts contrasted are not always of equal standing grammatically.” However, the point being made here is that other than a few occasions (e.g., John 7:49; Rom 5:15; 8:37; Gal 2:3), the main NT usage of ἀλλά is not introductorily, i.e., to initiate its own independent clause, but rather is connective and contrastive.

[4] For the “purpose” or “telic” function of the subordinating conjunction ἵνα, see Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 471-72. Additionally, Wallace has a noteworthy article regarding the usage of this conjunction at times being simultaneously “result-purpose” as there was no rigidly held distinction in the Semitic mind, cf. 473-74. This would help further enforce this author’s point that the man’s blindness was ordained by God with the purpose of Jesus one day healing the man, while also carrying the intended result of glorifying (revealing) Him in the process.

[5] Colin G. Kruse, The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 220.

[6] G. Campbell Morgan, The Gospel According to John (New York, NY: Revel, 1951), 165.

[7] Gary M. Burge, NIV Application Commentary: John (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), 272.

[8] Colin G. Kruse, The Gospel According to John, 220.

[9] G. Campbell Morgan, The Gospel According to John (New York, NY: Revel, 1951) 164-65.

[10] Gary M. Burge, TNIV Application Commentary: John, 272.

[11] All translations are this author’s.

[12] It is worth noting that none the scholars mentioned consider this aspect. This further proves how much presuppositions really do play an interpretive role in scholarship—even in the brightest thinkers.

[13] John MacArthur, Macarthur New Testament Commentary: John 1—11 (Chicago, IL: Moody, 2006), 393.

I think all of men’s ailments, due to a fallen nature and sin, make room for the Glory to be given to God when we are or it is changed and or healed. Regardless of the reason for blind man’s condition and why it was real for him, the point is that Jesus has power to heal and that God is the source of the power.

The good news is we will be changed anew someday anyway in our glorified bodies. Another thing I learn is that anything less than perfect in this life isn’t due to God’s lack of love or a specific sin of our own, but it should all point to the the result of sin in general. Beauty for example was with Jesus since Isaiah 53 says, regarding Jesus in verse 2, “there is no beauty that we should desire him.” So here is an example where physically Jesus wasn’t the best looking or “perfect”, even though He was in character. So being blind is different than outward beauty, but another example of where people’s bodies can fail due to working for the Lord’s glory is with Epaphroditus in Philippians 2:30 when it says, “Because for the work of Christ he was nigh unto death, not regarding his life, to supply your lack of service toward me.” Body are just not meant to last or be perfect.

If he doesn’t heal us in this life, He will in the next. In a lot of ways our less than perfect condition continues to testify of a need for God and the bodies limitations in a dying body. Praise God for a flawed body.

God predestination is a mystery, but we walk by faith and live out with contentment with what we have and what has been given. By the way I got lasik this month and now I see 20/20!

I got this regardless of where the comma is or was and even if it wasn’t there. I guess this is what they think about in seminary.

Thank you for this explanation. When God’s Word is analyzed using a literal grammatical historical hermeneutic, It does speak for Itself and man doesn’t make the oft-severe mistake of re-interpreting God’s Words for Him. I prefer to let God interpret His own Words and we simply read what He has to tell us.

I do wonder if a conclusion is made above that might be stretching John 9:3’s universal truth though. Allow me to ponder it this way:

The fact that God sometimes does something in no way means He always does this. For example, the Cessationists (and partial Cessationists) seem to make a good case for their position. God (and men) performed signs and wonders at key points in time, but whether He (and man) continue to do so as a rule today is difficult to justify. During Jesus’ ministry on earth, only a tiny SLIVER of total pages in the Bible, were healings, signs, wonders, and even an occasional raising of the dead took place. Satan and his minions certainly would have gone on full-force offense while He roamed the earth incarnate. Also know the Jews required signs and wonders.

But a little later, we see that Paul seemed dismissive of signs and wonders in so many ways.

I am NOT trying to use this platform to promote cessation. My goal is to use those arguments as an example of God doing things once in a while that do not seem to translate well across dispensations.

This is perhaps more sensitive to me because I was born with the minor annoyance of one leg and a grand total of three, deformed fingers. I read John 9:3 and get exactly the same conclusion you draw above. I do NOT see myself as being born this way as part of God’s master plan – other than His plan that expects us to be Godly while we go through trials of any kind, and ultimately He can use for good anything originally intended for evil. THAT seems to be a more universal message in Scripture that is cross-dispensational.

Here’s the thing. If I own an expensive crystal goblet and I drop it, I don’t blame Waterford Crystal that it broke. I blame myself.

In the same way, I blame man for the devolving state of health and morals and ethics in the world. When man chose to first sin, all bets were off on the gene pool remaining perfect. Until the ark when only one man was perfect in his generations, the world grew cold.

Think of the tower of Siloam that fell and killed 18. Although it’s only a short passage, the people asked Jesus why the tower fell and He answered, (paraphrased but I believe it’s in true context that we can agree), “They weren’t more guilty than anyone else, it just happened.” (This is immediately after they asked the same thing about Pilate’s handling of some Galileans’ deaths where Jesus basically replied with the same there-is-no-deep-meaning-here-it-occurred-because-man-is-man.) He immediately goes onto dismiss those questions about any possible deep meaning in the deaths and instructs His listeners how they are to behave no matter what their circumstances in life happens to be.

Please note, I do not think you imply that all handicapped people are that way because God made them handicapped. God forms us in the womb, but He surely never (or rarely) changes our sin-destroyed DNA before doing that. He forms us because He is the only author of life.

Once, when an evolutionist announced to the world that he can create life in his lab, he grabbed a flask of dirt to start the process. God immediately spoke up and said, “Not so fast, you make your OWN dirt.”

(Actually, that MIGHT not be in the Bible…)

Man seems to be able to destroy easily. We destroy ourselves easily. Our bodies are fallen and it was our choice that they are fallen. It’s the religion of evolution that man gets better, not worse over time, but they haven’t yet figured out a way to overcome those pesky Three Laws of Thermodynamics which belies their very foundation that man gets better over time.

It’s my educated guess that most on the 1024Project are either anti- or weak Calvinists. Certainly some are much stronger Calvinists. I can see the Calvinist’s position as being that all handicaps are designed by God specifically to bring about some ultimate purpose.

I just don’t think we can get that from Scripture alone.

John 9:3 certainly seems to say God had a specific purpose for THIS man. It seems God had a specific purpose for John before he was born. And several others. This man’s purpose happened to be tied to a physical problem. Unlike the majority of the healed lepers, God seems to be clear in teaching us this man’s purpose, whereas the lepers seem to just take their healing welfare and be bitter, not unlike most welfare recipients throughout history. What eternal, Godly purpose did they serve? I think a literal reading of Scripture can reveal none.

Again, I may very well be too sensitive given my own configuration, but I want to caution the thought that all handicaps are God-designed. God is the author of life and perfection. He gave us that 6000 to 7500 years ago. We dropped the crystal glass of perfect life and we should not blame the maker when we break ourselves.

I appreciate you allowing me to write all this. I broke Rule #1 in message responses which is KEEP IT SHORT and I ask your forgiveness on the wordiness of this message.

Yours because of Him,

Greg Perry