by Arnfield Cudal

– (Kamran is a Pakistani pastor who I met in Thailand. This is his story.)

I am Kamran from Kasur, Pakistan. I was born into a Christian family and at age fifteen I accepted Jesus Christ as my personal Savior. Pakistan is an Islamic country and ever since childhood, I felt a vast difference between Islam and Christianity. Here the Muslim majority frequently harasses Christians, but we’ve learned to live under this oppression and accept that religious discrimination and intimidation is a normal part of our life.

About eight years ago, I finished my Bachelor’s degree in Theology and began a small church on the street where our family and four other Christian families lived. According to the Pakistan Act of 1973, (religious) minorities are permitted to live their lives and practice their beliefs. But there is another law – the Blasphemy Law – which, if broken, is punishable by death. Regrettably this law is much misused, especially against Christians. I as a Christian felt that I am ready to die in the name of Christ, but not as a blasphemer of Islam.

Over the last six years, our church met regularly. We did everything we could to live at peace with the Muslim community around us. As our church grew, however, demands to minimize our activities began. We did what we could. For example, they asked us to not use speakers in our church services, so I stopped using it. Soon after, they demanded that we not gather to worship during Ramadan, and so for the whole month, we honored their request. We did our very best to honor and obey our Heavenly Father while at the same time live at peace with all men.

Two years ago, we invited a Christian singer who used traditional musical instruments to sing at our church. Apparently, this was too much for the Muslim community. They must not have liked how we used our country’s instruments to sing the Zaboors (Psalms). One Sunday, a group of Muslim men entered our church service and began firing gun shots into the air. Then they began beating me and our congregants with wood batons and rods. They took me at gunpoint and ordered me to stop having church. One of the church members managed to escape and the police were called. By the time they arrived everything, all the fixtures, equipment, and furnishings had been smashed to pieces. Two of the perpetrators were eventually caught and I was summoned to the station. After hearing my story however, the perpetrators were released and I, under pressure from the police chief, was compelled to recant the incident.

A few months earlier, I had come under the watchful eye of “Q”, a local religious leader and one of the key instigators. This time Q decided to use the Blasphemy Law against me.

June 5th, 2013, was a day in my life I will not forget. I received a call, “Aslam-o-alekum (Greetings) pastor, I am Saima. I need your help. My cousin’s sister isn’t well. If you pray for her she will be fine.” I asked her to be brought to church for prayer, but she replied that the sick girl was not capable of leaving the house. She insisted that I come to their house instead. After asking a few more questions, I learned that she was the daughter of Saima’s uncle, Q, the local imam who had been harassing me.

At first, the question came to my mind that if he disliked Christians so much, why would he have wanted me to come and pray for his daughter? Then I thought that perhaps God had changed his mind or perhaps because of their need, they wanted prayer. I discussed this with my wife and we both agreed that perhaps God had been working on his heart and that perhaps as a Christian pastor, my prayers might do her good and my gesture might be a good example to them. I made the decision to go to their house.

At her bedside, as I knelt to pray, an uncomfortable feeling overcame me. I sensed that someone was taking pictures of me. Scanning the room, I noticed a young boy holding a camera. At the time I thought that taking someone’s picture was a common occurrence and decided not to dwell on the thought that this could be a trap. I discounted the thought of how these pictures could potentially have negative consequences.

The very next day, June 6th, 2013, my fears came true. I received a desperate call from my wife who received this fatal letter:

“My Dear Muslim Brothers,

Today once again Kafir (an unbeliever) challenged the Muslims. Christian Pastor Kamran is a Kafir who is preaching Christianity and trying to convert our women. He tore the pages of the Holy Koran amongst the Muslim women in the absence of their husbands, brothers, and fathers who were away at work. Whoever finds him should cut off his hands and behead him. He is a Kafir. Whoever will not act accordingly will be an insult to Allah and his beloved prophet Muhammad (PBUH).” Issued by Q.

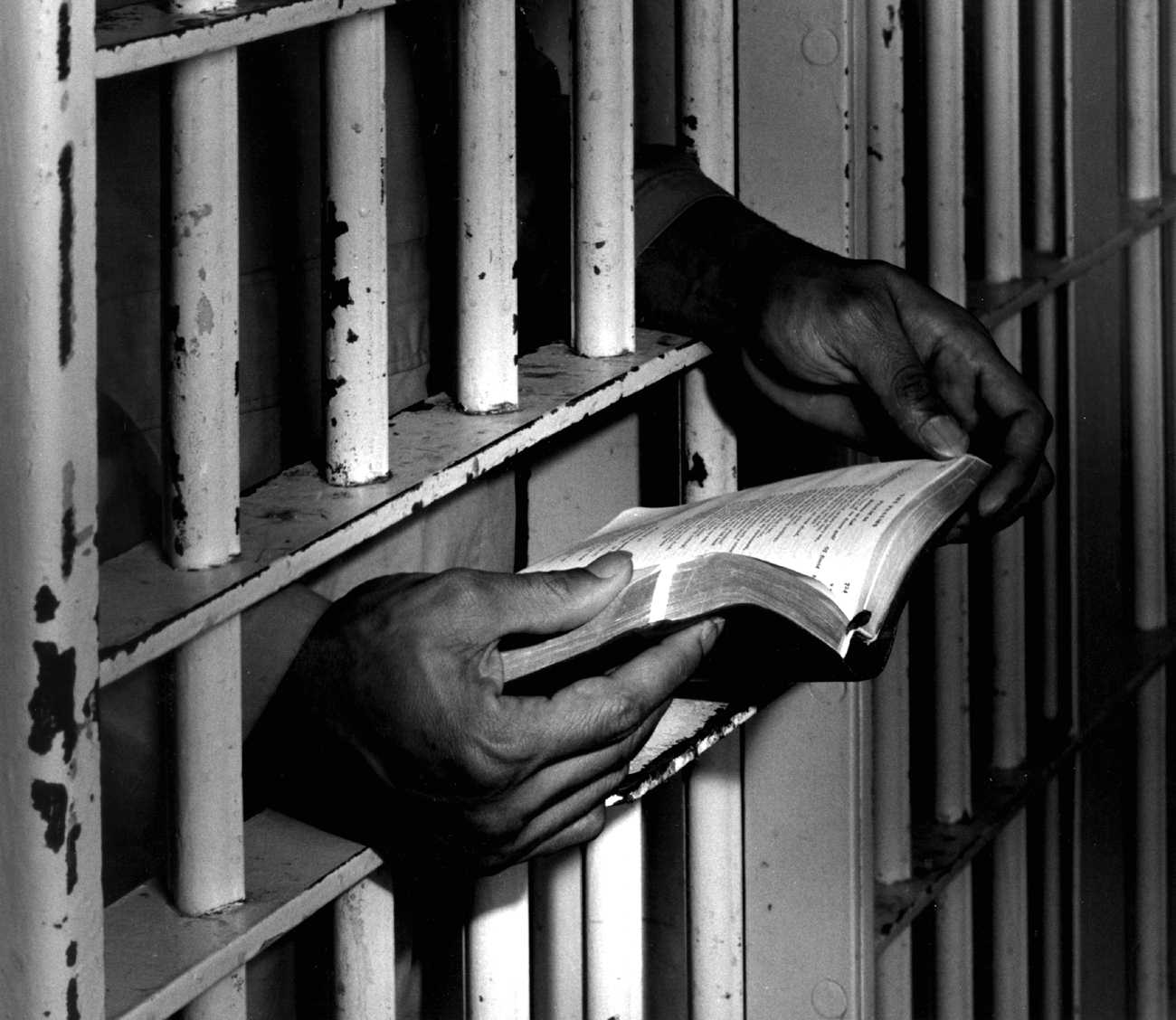

I realized that the pictures of me praying with a woman was strong irrefutable evidence for their case. I was terrified. Most Christians, after receiving a letter like this are killed on the spot by the mob. If they aren’t killed, they are arrested and are never released. I would never return home and see my pregnant wife and my son again. That very evening, one of the members informed me that the Muslim mob was looking for me and attempting to break into my house.

We managed to escape. Congregants from my church hastily collected some cash and sent us to another city, Faisalabad, to my sister-in-law’s house. It wasn’t but a few days before we had to flee again. Certain strangers had approached my sister-in-law asking for our whereabouts. We sought refuge at another Christian home but a local bishop urged us strongly that we leave the country. With blasphemy charges and a mob after us, we became fugitives, running from city to city, house to house with my now 36-week pregnant wife and son in tow. Since India, Nepal, Tibet, and Burma were not options, we decided go all the way to Thailand where we heard Christians are accepted, or at least, tolerated. After an extremely difficult month of hitch-hiking, walking, carrying and caring for my pregnant wife, and relying on the mercies of strangers, in July 2013 we arrived at the border of Thailand.

~ Kamran

It was last year, May, 2014, that I met Kamran and his family in Bangkok. I was in Thailand to conduct music at a 50th Anniversary of Filipino missionary work in Thailand in celebration of God’s faithfulness. The occasion promised to be a grand one, with members of the Bangkok Symphony, a Thai traditional orchestra, and an 80-voice intra-regional choir. Kamran was in this choir. He was the fellow, I recalled, that did not have proper black shoes to go with his choir uniform. He only had tattered sneakers and had to borrow someone else’s.

Following the celebration, Kamran’s wife, Rosie, invited us to dine at their house. We gladly accepted their invitation and looked forward to the Indian food she had promised. We arrived at the sparsely-furnished concrete flat next to an open market. The apartment belonged to a Thai Christian businessman who willingly lent his flat to this family, at least on a short-term basis. The scarcity and simplicity of the apartment indicated someone starting out from scratch. We began to feel a little embarrassed for accepting a promise of an elaborate meal. But in spite of the sweltering heat in the non-air conditioned flat, compounded by the heat from the kitchen, the hospitality was generous and the food delicious. The naan, or flat-bread, which had to be served hot right before the meal, was toasted on a flat skillet atop a propane tank. My wife Mary and I quickly realized that the feast of nihaari, pulao, kofte, lamb kebabs, qeema, and korma prepared for us must have taken hours. Rosie, Kamran’s wife, eventually admitted that preparations had begun eight hours earlier. She conceded that the food was prepared using the single skillet, atop the propane tank, and acknowledged that she had no stovetop, range, or oven to cook with in the kitchen! We were dumbfounded and speechless at their efficiency and labor of love.

Kamran recounted how they ended up in Thailand, adding humbly that he considers himself much more fortunate than his fellow Christian comrades who also have fled Pakistan. Christian refugees from Pakistan number in the thousands. He praised and thanked his quick-thinking church members who collected enough money for him to pay for a temporary visa into Thailand. He is also exceedingly grateful for American and Filipino missionaries he met at the border detention center who decided to take his family under their wing. His less fortunate comrades, who could not afford a visa, remain sequestered in detention centers. Kamran says he is on borrowed time and has to renew his visa monthly. He derives his meager support from benevolent missionaries who ask him to translate Bible class notes from English into Urdu. If Thailand does not extend his visa, he and his family will be detained in detention centers until someone or another country decides to grant him asylum. If Thailand decides to deport him, he will be transported back to Pakistan where he and his family face certain death. He is at the mercy of God and is thankful for his fellow Christians who provide him with whatever employment he can get.

We asked Kamran about his family and his recent marriage. He eagerly showed us their wedding album, and by looking through the pictures, we realized that he had come from an upper-middle class family in Pakistan — judging from the elaborate ceremony and festivities. The pictures were in stark contrast to the destitute fellow who had to resort to borrowing someone else’s shoes. He had had a large circle of friends, a large family, a loyal church following, and a relatively happy life, but all taken away in one swoop, for being followers of Jesus Christ.

Kamran is not bitter or resentful. He is grateful he still has his wife and children. But aside from having lost all else, as refugees in a foreign country, he says that there is one thing that has brought them through this very difficult time. Throughout their ordeal, no Bible in hand, they would sing the Zaboors, or Psalms.

As Kamran explained, Zaboor singing is a tradition for Christians in Pakistan. Every Sunday, the Psalms are sung, often three or four chapters at a time. Though they won’t be able to pinpoint chapter verses, once they begin singing a chapter, the rest simply follows. “It (Zaboor-singing) helps Christians in Pakistan keep their faith,” says Kamran. “…and we have all 150 (Psalms) memorized.”

That was one of the most fascinating statements all evening.

Later on, I decided to research and trace the lineage of Psalmody in Pakistan and India and discovered that the tradition of psalm-singing was an established one, a standard practice for worship services. Certainly psalm-singing is not an anomaly in Muslim countries, for the Zaboor is also a part of the Qur’an. Certain psalms of David, for example, are also included in the Islam canon and so psalm-singing is widely accepted and practiced.

However, it was mostly the work of Imam-ud Din Sahbaz, a Christian Punjabi convert in the early 1800’s, who took the practice of psalm-singing (exclusive psalmnody) from the United Presbyterian Church, and adapted the practice of whole-verse and metered singing to indigenous melodies (ragas) and rhythms (talas). Thus, Pakistani Christians have been in possession of the Psalms in their own language for nearly two centuries. Equally fascinating is how and why this tradition kept going strong.

This Eastern aspect of ecclesiastical history is as interesting the Western account, though less familiar. It is known that psalm-chanting or singing began in temple worship, continued in the synagogues, and spread to the Byzantines, Anglicans, and Puritans. Less documented is the practice of psalming as it passed through Arabia and toward India, though history and tradition has it that the Apostle Thomas continued his ministry into India.

Kamran asked me if I would like to hear him sing a Psalm. Recalling a tune I still had in mind, since I had just sung it for an Evensong service back in the States, I requested Psalm 84. Immediately, as though on cue, Kamran began in Urdu, “How lovely is thy dwelling place,” cantillating the metered text to a well-known raga. For Mary and I, unfamiliar with Urdu but clandestine fans of Bollywood-type music, quickly recognized the soulful and melodic ornamentation of the text. Kamran sang on with heartfelt emotion, “even the sparrow has found a home” and “better is one day in your courts.” He sang unaccompanied, his hands playing an imaginary harmonium. I imagined that a dholak (hand drums) and perhaps an algoza (flute) would complete the ensemble nicely.

Listening to Kamran sing the Psalms was exceedingly gratifying, enjoyable, and humbling at the same time. He described how a harmonium, often used to accompany congregational singing in Pakistan, was really a pipe organ consisting of maybe three octaves of about 40 reed pipes. One hand played the keyboard while the other worked the baffles like an accordion. He knew I was a pipe-organist as well, though I dared not compare that in our churches, I play on four keyboards, a pedal board, and that typhoon-type winds are pumped through 6000 – 8000 metal pipes.

But what impressed me immensely was Kamran’s memorization of the entire five books of the Psalms. Rosie spontaneously joined in. She has memorized the Psalm just as well. I realized they possessed a treasure incredibly valuable and meaningful.

I asked Kamran why he prefers the Psalms over our modern Christian songs. His response was truthful and straightforward, “When you endure such hardships and persecutions, you don’t want anything else. Modern Christian songs do not have what it takes to carry you through things like this. It is the pure word of God in the Psalms that help us keep our faith.”

Looking around his scant apartment once again, I tried to wrap my mind around my own existence. In a few days, I would be flying back to the Palm Beaches, Florida, where some of the residents ranked among the world’s most affluent. We have more churches and religious freedom than any country in the world, yet spiritually, we seem so much more impoverished. I mused at how we often pray that God should grant our request for a better job, or how we would like to have a nicer car, or what we’re going to wear, and complain when the restaurant didn’t cook the steak right – even after thanking God for the food. And here Kamran and Rosie had just spent all morning preparing our food, probably serving up their entire month’s food budget.

I couldn’t help but wonder about our Christian arts, music, and culture. Could it be that perhaps because of our prosperity, the songs of the Bible (e.g. psalms) are not as important or valuable to us as they are to Kamran?

I recalled one particularly sobering comment by an acquaintance who approached me about two years ago when I was spearheading a project putting the Psalms in Thai to traditional Thai music. He said, “Arnfield, why don’t you consider putting the Psalms to English first?” Though the question was genuine and sincere, my heart sank. The Psalms had been set to English since the Bible had been translated more than eight centuries ago.

Since the Canon of Scripture had been completed, for roughly five centuries after Pentecost, the church only sang songs of the Bible (psalms, hymns, spiritual songs). From the sixth century to this day, a lineage of Psalters (the Psalms set to music as hymnbooks) comprise a compendium of over thirty main Psalters since the fifth century. For example, as Christianity spread northward through the Caucuses, musicians compiled the Vepasian Psalter (800), the Paris Psalter (1000), and the Theodore (England) Psalter (1066). Eastward, there was the Kiev Psalter (1397), and the Psalter of Sofia. Westward to the New World came the Bay Psalm Book (1640) and the New England Psalter. Southward came the Yemeni Psalms and the Urdu Psalms (1825). For instance, The Genevan Psalter translated from the Latin Vulgate (John Day, 1562)[1] predated the completion of the 1611 King James Version of English Bible.

Now for the first time in Thailand’s history, just two years ago, twenty Psalms of the Bible were put to Thai traditional music. This event is particularly meaningful and momentous, considering that just about thirty to forty years ago, the notion of Thai music accompanying scriptures other than their own sacred texts (Sutras) was unthinkable. The Thais only sing psalms that are used to praise the King of Thailand. Yet decades of Christian work in Thailand has warmed the Thais to Christianity, and further inroads into the hearts and minds of the Thais using their soul-language, their music, are being laid.

Perhaps most regrettable of all, as I pondered my friend’s comment, is that mainline protestant and non-denominational churches today do not sing the Psalms. It is no wonder that the gentleman thought that the Psalms in English had not yet been set to music. I couldn’t help but wonder to what extent this unfortunate commentary had come to depict the state of our Western church. Have we become so soft, easy, and luxuriant that the Psalms have become a dispensable component of our Christian walk?

Just as our meeting with Kamran and his family that night reminded us that our fellow brothers and sisters in Christ throughout the world are undergoing persecution and are being maligned incessantly, we must reach deeper in our hearts and ask the question, what lessons can we learn from our persecuted brothers and sisters? Will our preference for the true word of God change?

If music is a barometer, at what point will we be able to say that the Psalms are considered important and valuable enough to be included in our services once again?

For now, I’ll take Kamran’s word. His trials and sacrifice far exceed what I could ever imagine. And I will take to heart what he said, “These days the Psalms really strengthen me in my hardships and trials because it is the direct Word of God – that’s why it’s more effective and powerful than any other songs.”

As Producer for HARK Music Publications, Arnfield oversaw and personally participated in the production of the first Thai Psalms Project – Ten Psalms of David and Ten Hallelujah Psalms, a recording of the Psalms in Thai set to Thai classical music, and Chiwit Mai (New Life), an album of hymn passages in the Bible set to Thai folk music. Both albums mark the first time in the Kingdom of Thailand that the Scriptures have been set in the native Thai style music. Arnfield is also a teacher-elder at their home fellowship church in West Palm Beach, FL. Their church uses the hymnbook: The Book of Psalms for Singing.[2]

Postscript:

As of March, 2015, Kamran’s temporary visa expired and his family faced imminent deportation back to Pakistan. The only alternative was a work visa at an “impossible” price of $4000. But with just days left, Christians around the world rallied to collect the funds necessary to keep Kamran’s family in Thailand at least another year.

Kamran is overjoyed and thankful for his worldwide Christian family. We at HARK decided to capture and record this moment. We are buying him a harmonium and decided to produce and record an album of Kamran’s favorite Psalms into a CD. This is the new Zaboor Project from HARK Music Publications.

[1]Laudemont Ministries www.laudemont.org/a-stp.htm (accessed April 15, 2015)

[2] Crown and Covenant Publications. http://www.crownandcovenant.com/The_Book_of_Psalms_for_Singing_s/35.htm

Thank you for sharing this,. A wonderful testimony . Will keep him in my prayers.