by David Gunn

– On November 13, 1618, the first session of the Synod of Dort was called to order. It would result in an indelible codification of Calvinistic soteriology that is still wildly popular some four centuries later. However, the chief purpose of the synod was not to produce a systematic soteriology, but rather to end a theological and historical controversy that had nearly brought Holland to the brink of religious civil war. This paper will attempt to sketch out a brief account of both the theological and political backgrounds to the historic synod, and thereby attain a better understanding of all the subtle nuances that influenced its convening and its outcome.

Theological Background

Since the primary concern of the Synod of Dort was the legitimacy or illegitimacy of Arminian theology, it is fitting to begin with mention of Arminius himself. The theological assault on Calvinistic thinking arose not from outside the walls of Calvinism, but from within. Jacobus Arminius served as a reformed pastor in Amsterdam from 1588 to 1603. Then in 1603 he was called away from the pastorate to teach theology at the University of Leiden, at which post he remained until his death in 1609.[1] During his most formative scholastic years, Arminius had studied at Geneva as a strict adherent to Calvinism and a disciple of Theodore Beza,[2] who is widely regarded to have first formulated supralapsarianism.[3] This is somewhat ironic given that the supralapsarian schema of soteriology was the immediate (though not the sole) cause of the Calvinist-Arminian conflict.[4]

Arminius first began to question his own Calvinistic theological system when confronted with the writings of Dirck Coornhert, a liberal thinker and proponent of religious tolerance, who had written forcefully against the high Calvinism espoused by theologians like Beza.[5] Arminius was asked to defend Calvinism against Coornhert’s onslaught, and in the process of doing so found that he could not defeat his opponent’s arguments.[6] After this, Arminius rethought his entire theological structure and became convinced of the doctrines of universal grace and the fundamental freedom of the human will.

Arminius’ departure from Calvinistic orthodoxy ignited a firestorm of controversy. Immediately there was conflict within the ranks of the Leiden University faculty, with Francis Gomarus, a loyal Calvinist and fellow professor of theology, opposing Arminius vociferously.[7] The controversy would get worse before it got better. After Arminius’ death in 1609, his theology was taken up and expanded by his disciple and friend, Simon Episcopius.[8] Immediately, Episcopius and likeminded followers of Arminius, calling themselves “Remonstrants,” petitioned the states of Holland requesting a reevaluation of the Netherland Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism, both of which reflected a highly Calvinistic form of theology.[9] At the invitation of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a supremely important Dutch statesman and moderate Calvinist (Oldenbarnevelt was himself a member of the Heidelberg community), forty-three leading Remonstrants came together on January 14, 1610, to formulate a written consensus of Remonstrant theology for official submission.[10] The principle framer of this document, Remonstrance, was John Uytenbogaert, a Dutch preacher and chaplain to Prince Maurice de Nassau.[11] This document outlined five articles which all forty-three Remonstrant representatives signed in July 1610. Briefly, the five articles of Remonstrance may be summarized as follows:[12]

(1) God has decreed Jesus Christ as the Redeemer of men and decreed to save all who believe on Him; (2) Christ died for all but only believers enjoy forgiveness of sins; (3) Man must be regenerated by the Spirit; (4) Grace is not irresistible; (5) Perseverance is granted through the assistance of the grace of the Holy Spirit, but whether one can fall away from life in Christ is left open. On the last of the five articles, it is worth noting that Arminius’ own position as well as that of the Remonstrants has been widely misunderstood. Their contention was not that Christians definitely can fall from grace and apostatize, but only that the Calvinist doctrine of the perseverance of the saints was illegitimately dogmatic and that the issue warranted further Scriptural examination before such a conclusive ruling should be reached.[13]

Almost immediately, the followers of Gomarus issued a Counter-Remonstrance, repudiating the five articles of the Remonstrants.[14] The Gomarists demanded a resolution to the conflict, and so Oldenbarnevelt arranged for a formal conference between the two groups in 1612. Since both groups were diametrically opposed theologically and desired different outcomes (the Remonstrants were primarily concerned to secure tolerance whereas the Gomarists desired conformity), the conference was a failure. Frustrated, Oldenbarnevelt simply commanded both groups to be tolerant of one another.[15]

This outcome was viewed by the Gomarists not as a compromise but as a victory for the Remonstrants, and the backlash was considerable. Oldenbarnevelt had mistakenly assumed that the interest in this issue was mostly limited to the academic elite in their ivory towers. Quite to the contrary, the conflict manifested itself in both scholarly and common circles. When Gomarist ministers were stripped of their posts by magistrates favoring the Remonstrants, public rioting began.[16] One account is even told of a Calvinist blacksmith chasing Episcopius down the street with a red-hot iron, seeking to physically brand him a heretic.[17] Things quickly spiraled out of control, the conflict found itself in a vice-like gridlock, and the prospect of outright civil war loomed on the horizon. The Gomarists had expressed desire to resolve the situation by means of a national synod, but both Oldenbarnevelt and the magistrates had refused, knowing full well that such a synod would likely favor the Gomarists and see the Remonstrants (toward whom Oldenbarnevelt and the magistrates were sympathetic) charged as heretics.[18] And so it fell to Maurice de Nassau, Prince of Orange, to settle the matter. Although Maurice had no theological stake in the controversy (indeed, he once confessed that he “did not know whether predestination [was] blue or green),[19] he decided in 1617 to favor the Gomarists for primarily political reasons.[20] Using his command of the army as leverage, he insisted that the magistrates permit the convening of a national synod which would resolve matters decisively.[21] Oldenbarnevelt’s attempts to forestall the Synod of Dort had failed. The Remonstrants would have to submit to a national synod for evaluation and judgment.

Political Background

The events leading up to the Synod of Dort must be seen against the backdrop of the Dutch War of Independence (1568-1648). William I, Prince of Orange (1533-1584) had been by all accounts the preeminent Dutch hero of the war. In 1566, the Dutch people took William as their leader, and beginning with an army of 30,000 he proceeded to win decisive victories over the Spanish.[22] In July 1581, toward the end of William’s career, the States General of Holland signed and issued their Declaration of Independence from Spain.[23] Three years later, on July 10 1584, William was assassinated.[24] From 1582-1584, there had been no fewer than five separate assassination attempts on William’s life, all of them sanctioned and commissioned by Spain.[25] The sixth would be the last.

After William’s death, his power and influence passed to his second legitimate son, Maurice de Nassau.[26] Maurice proved to be very capable, and under his leadership the Dutch independence for which William had striven finally became a reality. This was due in no small part to the wise tutelage and counsel of Oldenbarnevelt, Maurice’s mentor.[27] However, as Maurice’s career progressed, his relationship with Oldenbarnevelt became strained. Maurice harbored deep-seated resentment against the Spanish, and Oldenbarnevelt wished to see peaceful diplomatic relations forged between Spain and Holland. In fact, Oldenbarnevelt in his political station as Landsadvocaat had signed the Twelve Years’ Truce with Spain in 1609, which Maurice vehemently opposed.[28] Maurice had not been prepared to countenance any peaceful relationship with Spain, which is precisely what Oldenbarnevelt had secured. It became immediately apparent that the two politicians’ governing philosophies were incompatible, and Maurice began to resent Oldenbarnevelt for acting contrary to his wishes. And so, just as Jacobus Arminius had turned on his mentor Beza years earlier, so too Maurice turned on his mentor Oldenbarnevelt. When Oldenbarnevelt threw his support behind the Remonstrants, the Calvinists openly declared their support for Maurice.[29] Thus, an unholy symbiosis of political and religious conflict emerged. By siding with the Calvinists, Maurice could use the cloak of religious solidarity to secure a victory over Oldenbarnevelt and consolidate his own political power over Holland.

Of course, Maurice and Oldenbarnevelt were not the only two rivals in Holland at this point in her history. Although one might at first blush envision independent Holland as monolithic and united, this simply was not the case. What union between the disparate factions did exist had been forged by a long and costly war, and emerged more out of convenience than conviction. Many cities and provinces held long and bitter rivalries with other cities and provinces, and when it came time to declare either for the Remonstrants or the Gomarists, the old prejudices came rising to the surface. When Rotterdam came out in support of the Remonstrants, Amsterdam appears to have declared for the Gomarists solely because of the longstanding rivalry between the two cities.[30]

Additionally, the Netherlands were at this time witnessing a growing divide between the merchant class on one side and the clergy and commoners on the other. Like Odenbarnevelt, many of the merchants desired a peaceful relationship between Holland and Spain. Such a relationship would have been tremendously beneficial to the merchant class, since many goods could then be imported from Spain. The clergy on the other hand were staunchly opposed to any peaceful relationship with Spain, given its deeply entrenched Roman Catholicism. Any such relationship would necessarily include a measure of mutual religious tolerance, and the Reformed ministers had no desire to see the spiritual purity of their churches polluted by the great Roman beast. Most of the commoners sided with the clergy: they possessed a strong sense of nationalism since Holland’s independence was still such a recent phenomenon, and commensurate with that, a strong loyalty to Calvinism too. To make matters worse, the merchants had in many cities become a virtual oligarchy all of their own, and that flew in the face of Prince Maurice’s authority. The commoners resented the merchants for their wealth and power, and Maurice begrudged them their growing influence. When the Calvinist-Arminian conflict reared its ugly head, the merchant class proved sympathetic to the moderate Remonstrants under the leadership of Oldenbarnevelt, while the commoners and clergy favored the Counter-Remonstrants under the leadership of the hardliner Gomarus.[31]

Under these circumstances, it was inevitable that Prince Maurice would strongly favor the Gomarists, and a national synod seemed the most straightforward way of securing a slam-dunk victory for them. If Maurice was going to have a war it would be a war with Spain, not a Dutch civil war, and so the Remonstrant defeat would have to be swift and decisive. First, Maurice arrested Oldenbarnavelt along with Hugo Grotius, another influential Remonstrant supporter.[32] Next, Maurice forcibly removed pro-Remonstrant magistrates from their offices and replaced them with magistrates who favored the Calvinists.[33] When the Synod of Dort convened, the deck had already been stacked in the Gomarists’ favor. The downfall of Gomarus’ theological opponents and Maurice’s political opponents was now only a matter of time.

The Synod of Dort

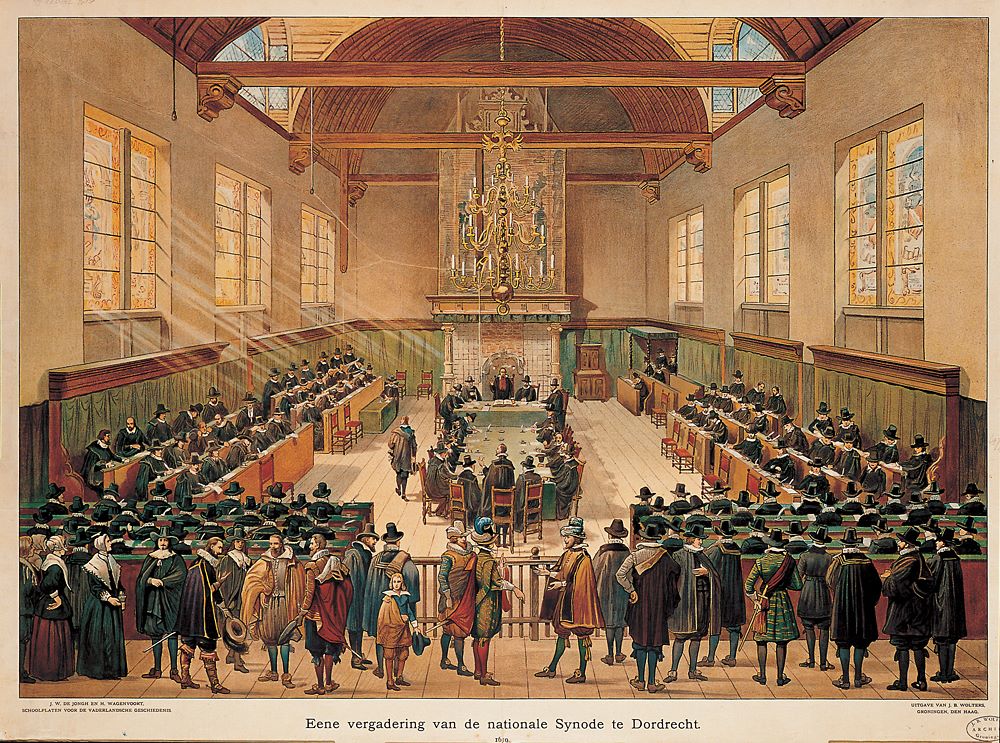

The time had come for the matter to be decided. The States-General called for a Synod to meet at Dortrecht. The synod could be categorized a national synod in that the synod’s decision would apply specifically to the situation in Holland. At the same time, the theological implications would have geographically far-reaching ramifications, and so non-Dutch delegates also took part in the synod. That being the case, it is equally valid to consider the Synod of Dort an international synod.

Some one-hundred delegates met for the synod. There were thirty-five Dutch clergymen accompanied by Dutch elders, six deputies representing the States-General, five theology professors from Dutch universities, and twenty-seven delegates from foreign countries.[34] The most powerful and influential foreign delegates were the five representatives of England. An invitation had been extended to the French Huguenots, but they were forbidden from attending by King Louis XIII.[35] Initially, three Remonstrants from Utrecht managed to gain appointment as delegates, but they were immediately rejected from consideration and replaced with Gomarist appointees.[36] Sixteen Remonstrant clergymen in addition to Episcopius were sent to the synod to defend Remonstrant theology. They were granted admission, but not as official delegates.[37] They would be permitted to speak in their own defense, but had no real power to influence the synod’s decision.

The Remonstrants spoke boldly and passionately in defense of their views. On the twenty-third session, Episcopius delivered a rousing speech that was “praised for its power (but criticized for its length).”[38] The clashes between the Remonstrant representatives and the other delegates became more and more vehement, and the Remonstrants came to be viewed as disorderly obstructionists.[39] Eventually, the synod’s president, Johannes Bogermannus, angrily dismissed the Remonstrants from the synod.[40] The synod continued without any Remonstrant representation at all.

It is important to keep in mind, on the other hand, that the Calvinist delegates did not constitute an entirely united front. Calvinist theology was by no means monolithic at this point in time, and the subject of the extent of the atonement generated much heated debate between the reformed delegates.[41] The debate became so heated that on two separate occasions Gomarus, who held to the limited atonement view, challenged Martinius, who favored unlimited atonement, to a duel.[42] Two important unlimited atonement advocates were English delegates John Davenant and Samuel Ward. Davenant at one point proclaimed that he would rather have “his right hand cut off” than embrace a limited atonement view.[43] (Presumably, Gomarus would have been happy to oblige him!) Although the synod did finally decide in favor of a limited atonement, the proceedings of Dort nevertheless manifested the seeds that would shortly thereafter blossom into Amyraldianism.

After 180 sessions in 128 days (all of which was paid for, including compensation for the delegates, by the States-General),[44] the synod condemned the Remonstrants as heterodox and unanimously signed the Canons of Dort.[45] The Canons, framed in express contradistinction to the five articles of Remonstrance, may be summarized as follows:[46]

(1) God’s eternal decree of predestination is the cause of election and reprobation, and that this decree is not based upon foreseen faith; (2) Christ died for the elect only; (3) Men by nature are unable to seek God apart from the Spirit; (4) Grace is irresistible; (5) The elect will surely persevere in faith to the end. These are the five points of the common acronym TULIP, although they were not originally framed in that order. It is worth mentioning that the Remontrants’ understanding of total depravity has frequently been misunderstood. In fact, both they and the Synod of Dort held that humans are totally depraved. The only fundamental difference between the two theological schemas on that point was that the Remonstrants refused to establish a link between total depravity and irresistible grace, whereas the synod established such a link as the primary means whereby a person is drawn to the gospel.[47] To espouse that either Arminius or the Remonstrants embraced a form of Pelagianism would be entirely erroneous.

The Aftermath

The Synod of Dort concluded on May 9, 1619. The five points of Calvinism had been codified and the followers of Arminius had been univocally condemned. The immediate ramifications of these decisions were harsh and decidedly uncharitable. The Remonstrants and their allies were given an option: either recant, or submit to imprisonment or exile. Very few were willing to recant, and so over 200 Remonstrant teachers and preachers were banished. Many of them gathered in Antwerp, and there formed the Remonstrant Reformed Brotherhood.[48] The state commissioned spies to hunt down any Remonstrants suspected of sneaking back into Holland.[49] Grotius was sentenced to life imprisonment, but shortly thereafter managed to escape in a chest ostensibly filled with books thanks to the cunning resourcefulness of his wife.[50] As for Oldenbarnevelt, Maurice arranged for him to be convicted on a trumped-up charge of treason and executed.[51] This was done amid public outcry and manifold pleas for Maurice to issue Oldenbarnevelt a pardon, for the latter had overwhelming public popularity.[52] Maurice would have none of it; regardless of the potential political backlash, he was determined to do away with his political rival once and for all. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt was beheaded on May 13, 1619.[53]

In the short-term, Dort’s decision rendered matters rather bleak for the Remonstrants. They had been condemned for being “preachers of error, introducers of novelties, and creators of schisms.”[54] It is ironic that children of the Reformation could be so quick to judge one another on this basis, as the entire Protestant Reformation had been roundly condemned by Rome for precisely the same reasons.

In the long-term, however, Dort’s implications were far less determinative than the Gomarists would have preferred. After Maurice died of liver failure on April 23, 1625 (he had been a relentless drinker),[55] his brother Frederick Henry took the throne. While Calvinism continued to enjoy recognition as the official religion of the Netherlands, Frederick preferred a light-handed approach to religious dissention and extended to the Remonstrants the religious tolerance they had long sought.[56] The Remonstrants returned to Holland en masse, planted Remonstrant congregations, and freely taught Arminian theology.[57] Moreover, the synod’s decision proved fairly ineffectual on the international scene. In England, King James I, who had initially supported the Synod of Dort and personally appointed the English delegates,[58] later withdrew his support from the synod’s decision and, for political reasons, forbade the public preaching of Dortian theology.[59]

Arminianism, having returned to its homeland, gradually gained increasing support in the Reformed church. It would enter the Church of England under the Stuarts, and then gain international prominence with the eventual rise of Methodism under John Wesley.[60] As for the moderate Calvinism of Davenant, Ward, and Martinius, it too would soon blossom under the teaching and theologizing of Moyse Amyraut.[61] Out of the Saumur Academy arose an attempt on the part of Amyraut and likeminded professors of theology to “tone down the rigorous Calvinism of the Synod of Dort.”[62] The unlimited atonement theology of Amyraldianism was born, and began to gain prominence in the 1630’s.[63]

And yet, although the Canons of Dort did not have the far-reaching and conclusive results that the synod no doubt desired, nevertheless the theological importance of Calvinism’s five points cannot be denied. This quinquarticular formulation of Calvinistic soteriology continues to dominate theological discussion and debates to this day, and reflects the logically deductive and internally coherent schema to which loyal Calvinists subscribe the world over. No doubt many today would decry the synod’s harsh and unchristian judgment on its opponents, but the Canons continue to be read, questioned, admired, and defended four centuries later.

Bibliography

Anderson, David R. “Another Tale of Two Cities.” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society 18 (Autumn 2005): 51-75.

Augustijn, Cornelus. “Dordrecht, Synod of.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 2:2-3. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996.

Bangs, Carl. “Arminius, Jacobus.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 3:72-73. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996.

———. “Episcopius, Simon.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 2:54-55. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996.

Berkhof, Louis. History of Christian Doctrines. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1985.

Berridge, Geoff, and Thomas G. Otte. Diplomatic theory from Machiavelli to Kissinger. Chippenham, Wiltshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Calder, Frederick. Memoirs of Simon Episcopius. London: Simpkin and Marshall, 1835.

Daniel, Curt. The History and Theology of Calvinism. 1st ed. n.p.: Scholarly Reprints, 1993.

Davis, John Jefferson. “The Perseverance of the Saints: A History of the Doctrine.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 34, no. 2 (June 1991): 213-222.

Devreese, Jozef T., and Guido Vanden Berghe. ‘Magic Is No Magic’: The Wonderful World of Simon Stevin. Ashurst, Southampton: WIT Press, 2008.

Gilmore, Geo W. “Episcopius (Bisschop), Simon.” In The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 2:159-160. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950.

Godfrey, W. Robert. “Reformed Thought on the Extent of the Atonement to 1618.” Westminster Theological Journal 37, no. 1 (1974): 133-171.

Gonzalez, Justo L. A History of Christian Thought. Vol. 3. New York: Abingdon Press, 1975.

———. The Story of Christianity: Reformation to the Present Day. Vol. 2. 1st ed. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985.

Groenveld, S. “Oldenbarnevelt, Johan van.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 3:172-173. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Hales, John, Peter Gunning, and John Pearson. Golden remains, of the ever memorable Mr. John Hales … London: Printed by T. B. for G. Pawlet, 1688.

Heick, Otto W. A History of Christian Thought. Vol. 2. Philadephia: Fortress Press, 1966.

Israel, Jonathan. The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1998.

Jardine, Lisa. The awful end of Prince William the Silent: the first assassination of a head of state with a handgun. London: HarperCollins, 2005.

McNeill, J.T. The History and Character of Calvinism. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1967.

Milton, Anthony. The British Delegation and the Synod of Dort (1618-19). New York: Boydell Press, 2005.

Motley, John Lothrop. The Rise of the Dutch Republic. Vol. 3. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856.

Olson, Roger E. The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. First Edition. IVP Academic, 1999.

Picirilli, Robert E. Grace, Faith, Free Will. Nashville: Randall House Publications, 2002.

Rogge, H. C. “Dort, Synod of.” In The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 3:494-495. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950.

———. “Remonstrants.” In The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 9:481-483. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950.

Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church. Vol. 8. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1910.

———. The Creeds of Christendom. Vol. 3. 6th ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2007.

Stevens, Harm. Shades of Orange: a history of the royal house of the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2001.

Strehle, Stephen. “The Extent of the Ateonement and the Synod of Dort.” Westminster Theological Journal 51 (1989): 1-23.

Tex, J. Den. Oldenbarnevelt: 1606-1619. New York: CUP Archive, 1973.

Thatcher, Oliver J. The Library of Original Sources: Volume V (9th to 16th Century). Milwaukee: The Minerva Group, Inc., 2004.

Vink, Marcus P. M. “Grotius, Hugo.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 2:197-198. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996.

[1] Carl Bangs, “Arminius, Jacobus,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, vol. 3 (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996), 73.

[2] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1967), 263.

[3] Roger E. Olson, The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform, First Edition. (IVP Academic, 1999), 456.

[4] Otto W. Heick, A History of Christian Thought, vol. 2 (Philadephia: Fortress Press, 1966), 64.

[5] Ibid., 65.

[6] John Jefferson Davis, “The Perseverance of the Saints: A History of the Doctrine,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 34, no. 2 (June 1991): 221.

[7] Heick, A History of Christian Thought, 65.

[8] Geo Geo W. Gilmore, “Episcopius (Bisschop), Simon,” in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950), 159.

[9] H. C. Rogge, “Remonstrants,” in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, vol. 9 (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950), 481.

[10] Ibid.

[11] This put in motion events that would result in a shattering of the previously warm relationship between Uytenbogaert and Prince Maurice.

[12] David R. Anderson, “Another Tale of Two Cities,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society 18 (Autumn 2005): 72.

[13] John J. Davis, “The Perseverance of the Saints,” 221-22.

[14] McNeill, 264.

[15] S. Groenveld, “Oldenbarnevelt, Johan van,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, vol. 3 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 172.

[16] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 264.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Jonathan Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806 (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1998), 421-426.

[19] One is reminded of Emperor Constantine who called the Council of Nicaea and moved for theological solidarity primarily for political reasons, probably not because of any strong theological convictions.

[20] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 264-65.

[21] S. Groenveld, “Oldenbarnevelt, Johan van,” 173.

[22] Oliver J. Thatcher, The Library of Original Sources: Volume V (9th to 16th Century) (Milwaukee: The Minerva Group, Inc., 2004), 189.

[23] Ibid., 190-97.

[24] Lisa Jardine, The awful end of Prince William the Silent: the first assassination of a head of state with a handgun (London: HarperCollins, 2005), 46.

[25] John Lothrop Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic, vol. 3 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856), 597.

[26] Maurice’s older legitimate half-brother, Philip, was still alive at this time. However, since he was imprisoned in Spain at this time, he was of no real use to Holland.

[27] Geoff Berridge and Thomas G. Otte, Diplomatic theory from Machiavelli to Kissinger (Chippenham, Wiltshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 50.

[28] Jozef T. Devreese and Guido Vanden Berghe, ‘Magic Is No Magic’: The Wonderful World of Simon Stevin (Ashurst, Southampton: WIT Press, 2008), 48.

[29] Jonathan Israel, The Dutch Republic, 431.

[30] Justo L. Gonzalez, A History of Christian Thought, vol. 3 (New York: Abingdon Press, 1975), 258.

[31] Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity: Reformation to the Present Day, vol. 2, 1st ed. (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985), 180-81.

[32] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 265.

[33] Robert E. Picirilli, Grace, Faith, Free Will (Nashville: Randall House Publications, 2002), 14-16.

[34] H. C. Rogge, “Dort, Synod of,” in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, vol. 3 (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1950), 494.

[35] Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity v.2, 181.

[36] Robert E. Picirilli, Grace, Faith, Free Will, 15-16.

[37] Curt Daniel, The History and Theology of Calvinism, 1st ed. (n.p.: Scholarly Reprints, 1993), 38.

[38] Carl Bangs, “Episcopius, Simon,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996), 55.

[39] To be fair, the Remonstrants were dealt an incredibly unplayable hand, and they knew it. It is easy to understand why they would have found a synod completely stacked against them to be frustrating and disheartening.

[40] Curt Daniel, The History and Theology of Calvinism, 39.

[41] W. Robert Godfrey, “Reformed Thought on the Extent of the Atonement to 1618,” Westminster Theological Journal 37, no. 1 (1974): 133.

[42] John Hales, Peter Gunning, and John Pearson, Golden remains, of the ever memorable Mr. John Hales … (London: Printed by T. B. for G. Pawlet, 1688), 470, 577.

[43] Ibid., 577-78, 581.

[44] Cornelus Augustijn, “Dordrecht, Synod of,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996), 2.

[45] Curt Daniel, The History and Theology of Calvinism, 39.

[46] David R. Anderson, “Another Tale of Two Cities,” 72.

[47] Just L. Gonzalez, A History of Christian Thought v.3, 259-60.

[48] H. C. Rogge, “Remonstrants,” 482.

[49] Robert E. Picirilli, Grace, Faith, Free Will, 16.

[50] Marcus P. M. Vink, “Grotius, Hugo,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1996), 198.

[51] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 265.

[52] J. Den Tex, Oldenbarnevelt: 1606-1619 (New York: CUP Archive, 1973), 673ff.

[53] S. Groenveld, “Oldenbarnevelt, Johan van,” 173.

[54] Frederick Calder, Memoirs of Simon Episcopius (London: Simpkin and Marshall, 1835), 365.

[55] Harm Stevens, Shades of Orange: a history of the royal house of the Netherlands (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2001), 10.

[56] Stephen Strehle, “The Extent of the Ateonement and the Synod of Dort,” Westminster Theological Journal 51 (1989): 21.

[57] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 266.

[58] Anthony Milton, The British Delegation and the Synod of Dort (1618-19) (New York: Boydell Press, 2005), 92-94.

[59] Stephen Strehle, “The Extent of the Atonement and the Synod of Dort,” 21-22.

[60] Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 8 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1910), 815.

[61] Stephen Strehle, “The Extent of the Atonement and the Synod of Dort,” 23.

[62] Louis Berkhof, History of Christian Doctrines (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1985), 190.

[63] J. T. McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 314.